History

Much of the following historical record is distilled from several monographs featured in “Affordable Dreams: The Goetsch-Winckler House and Frank Lloyd Wright” (ISBN: 1-879147-12-2), a special issue of Michigan State University’s Kresge Art Museum Bulletin published in 1991 and the definitive treatise on the subject of the Goetsch–Winckler house and its original owners. More information about how to obtain a copy of this book can be found here.

If not for the diligent research conducted by the book’s contributing authors, much of the home’s history would surely have been lost to time. To say that we are grateful would be an understatement.

Before Wright

Alma Goetsch (1901–1968) and Kathrine Winckler (1898–1976) were both born and raised in Wisconsin at the turn of the twentieth century. Awareness of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work and architectural philosophy was not uncommon among artistically inclined Wisconsinites, but Winckler had a particular advantage: her father had been Wright’s classmate at the same grade school she herself later attended.1

Portraits of Alma Goetsch (with Littlebit) and Kathrine Winckler.

Courtesy the Michigan State University Archives and Historical Collections.

Goetsch and Winckler both valued independence, free thought, and social consciousness, and were among the many tenacious Midwestern women of their generation who earned college degrees.

Winckler received her Bachelor of Arts from the University of Wisconsin in 1921 and started her career in Chicago, where she worked for several years as a commercial artist. At around the same time, Goetsch enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago, where she earned a Bachelor of Arts in Education in 1928.2

In 1926, Winckler moved to Michigan to teach art at Michigan State University (then Michigan Agricultural College). Two years later, Goetsch accepted a similar position—and it was there that the two women met, beginning a lifelong partnership that would shape both their personal and professional lives.3

Kathrine Winckler, “Still Life with Sculptures”, oil on Masonite, unknown year.

Notably, at the time, it was considered improper for unmarried women to live alone. According to Winckler’s sister, Salome Winckler Wells, the two women began living together as roommates in 1931 after finding a suitable apartment to share.4

However, they remained dissatisfied with their living conditions. As Winckler later wrote, “All my life I have resented the little holes in walls that people call windows.”5

Both women were deeply familiar with Frank Lloyd Wright’s work and architectural philosophy, and long dreamed of commissioning a home that embodied his ideals. It was a dream that seemed unattainable—that is, until Wright developed the first moderate-cost Usonian house. Only then did they “dream that heaven was within our reach.”6

Street view of the Jacobs House / © The Estate of Pedro E. Guerrero.

Winckler became a frequent visitor to the Jacobs House in Wisconsin, Wright’s first Usonian design, admitting, “I finally became apologetic about it.”7 She also consulted Wright directly about building a home, but when the opportunity arose to participate in a cooperative housing project near Michigan State, the dream they had long cherished finally seemed possible.

Usonia II

Michigan State’s first encounter with Wright was in 1935 when the landscape architecture department at Michigan State invited him to campus. There he delivered a lecture on organic architecture titled “In the Nature of Materials,” where he discussed the importance of harmony between structure and environment.8

Just a few years later, in the wake of the Great Depression, campus housing remained scarce and was dominated by Colonial Revival, Tudor, and generic “builder’s box” styles—like Goetsch and Winckler’s apartment. Seeking alternatives, Michigan State professors Sidney Newman and Harold Fields optioned forty acres at the southeast edge of the Michigan State campus to establish a cooperative of modestly priced homes for faculty.9

Early participants, including members of the art department such as Goetsch and Winckler, were especially enthusiastic about Wright’s work and conveyed their interest to Newman. By August 1938, seventeen acres were reserved for homes designed by Wright, with plans for seven houses arranged around a central caretaker’s cottage.10

Courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ.

In their correspondence with Wright’s office, the group understood that, while Wright insisted on creative freedom, he still needed to understand his clients’ daily lives. Each participant penned a letter describing their family, routines, interests, and idiosyncracies so that they might be taken into account in his designs.11

Goetsch and Winckler introduced themselves as energetic art teachers in their forties with “a common desire to have you build a house for us.” Winckler noted, “I am unhappy unless I can cross my long legs under the table,” and she recalled her awe at the view from the Jacobs House bedroom: “the earth and trees and sky all at once.”12

Goetsch admitted some unease “moving to the country” and asked Wright to design a bedroom that felt secure: “Although I am only 5’2", I manage to fight my battles all right while awake.” She also added, “Please put a few pantry shelves down where I can reach them.”13

The cooperative hired Harold Turner, a Danish-American builder who had previously worked with Wright on several other Usonian homes, to supervise the project and turn Wright’s designs into reality.14

Harold Turner onsite at Hanna House.

© 1981 Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hanna House: The Client’s Report.

Unfortunately, in September 1939, just as construction was to begin, the project’s financier withdrew. Despite efforts—including Wright’s direct appeal to the Federal Housing Authority—no lender was willing to back the venture. By mid-1940, the project was abandoned.15

Goetsch and Winckler remained undeterred. They secured their own financing by pooling their savings and using Winckler’s mother’s home as collateral.16 In all, they budgeted $6,600 for the construction of their home—equivalent to about $150k in 2025.17 They then wrote to Wright, “We have our money. When may we start?”18

But there was a problem: the piggery next door. The vacant lot adjacent to the planned site for Goetsch and Winckler’s home was being used by the city of East Lansing as a garbage dumping ground, and a hog wallow sat nearby where pigs were fed trash.19

Dissuaded by the piggery next door, the women purchased a more “attractive” plot of land in April 1940, with similar terrain about a mile southeast of the original site, and broke ground two months later on June 4.20

They quickly sent a letter to inform Wright of their progress: “Our house is started!”21

Construction Begins

Of all the participants in the Usonia II project, Goetsch and Winckler made the fewest specific requests. The two had an intimate familiarity of Wright’s work and philosophy, and trusted in his expertise to create a home that would meet their every need without detailed direction.22

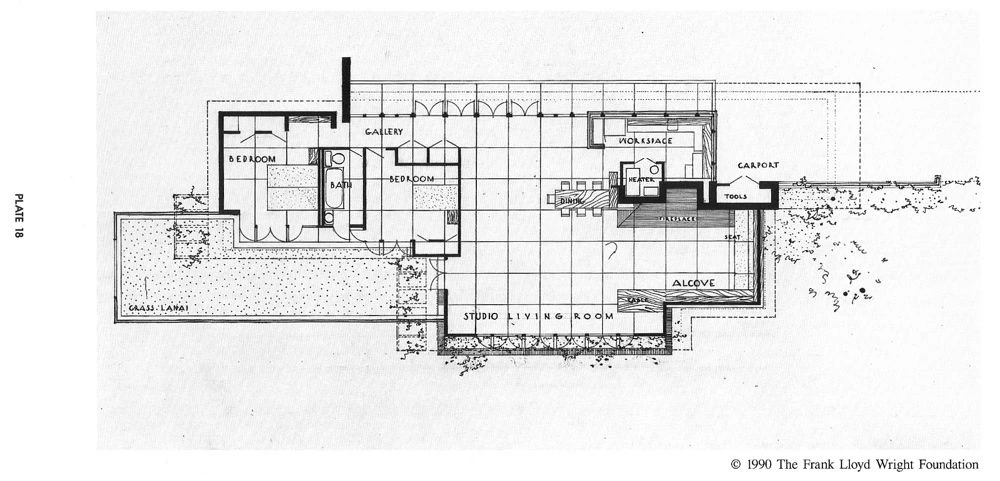

To accommodate their love of entertaining and various artistic pursuits within a modest footprint, Wright designed an open, airy space flanked by friezes of windows. He called this central area the “Studio-Living Room.”23 The open floor plan subtly defined distinct yet interconnected areas, including a snug corner for reading and conversation centered around a warm, inviting hearth.

The dining table system was designed to be modular, with four mobile sections that could serve as individual tables or extend the built-in units for dining or creative work. The result was a flexible and thoughtfully designed interior that functioned with elegance and ease.

Goetsch–Winckler floorplan / © 1990 The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Goetsch and Winckler were perfectly suited for the informal style of living and entertaining, but while Goetsch and Winckler were “entranced beyond words” when they received their blueprints for the home, there was one thing that was missing: a place to store their preserves.24

Goetsch and Winckler had asked Wright for a cool place in which to store jams and jellies, but he repeatedly declined, urging them to find alternative arrangements. The women were unable to do so, nor had they found adequate storage for their dishes, pottery, and glass.25

Frank Lloyd Wright was well-known for avoiding cellars and garages, believing such spaces encouraged clutter.26 Although some later Usonian homes did incorporate cellars, the Goetsch–Winckler House, as one of his earliest Usonian designs, reflected Wright’s unwillingness at the time to compromise on his principles.

Instead, they turned to their builder, Harold Turner.

“Disturbing Changes”

Not long after breaking ground, Turner realized that construction costs were projected to exceed Goetsch and Winckler’s budget. To keep expenses within limits, several modifications were made.

Turner informed Wright that he needed to substitute the specified cypress siding with cheaper and more easily-sourced redwood. The ceiling, originally designed with thin redwood boards, was replaced with four-foot-square oiled plywood panels. To further economize, he omitted the decorative perforated boards—sometimes called “shadow screens”—that were intended for the clerestory windows.27

Turner then cleverly converted the outdoor “Tool Storage” cabinet into a staircase which led down to a root cellar underneath the carport. Finally, after Goetsch and Winckler requested more kitchen space, he excavated an area beneath the studio-living room to house the water heater and boiler, which had originally been located in the workspace.28

Harold Turner’s alterations ultimately proved effective: the home was completed with just $5.27 to spare29—a rare and possibly singular example of a Wright-designed home that did not exceed its budget.

However, upon learning of the modifications, Wright was less than pleased. When Goetsch and Winckler traveled to Taliesin on August 15 to express their appreciation for the home, they were instead met with a letter ordering them to stop paying Turner, “until I have a chance to do the work necessary to put the work back in proper form.” Wright then went so far as to threaten that he would refuse to recognize the house as an authentic work.30

Goetsch and Winckler, however, stood by Turner’s integrity and urged Wright to see their house for himself declaring “We feel now that we have one of the very finest [Frank Lloyd Wright houses].”31

In a rare concession, Wright relented after speaking with Turner directly:

"Dear Misses Goetsch and Winckler: Harold Turner came down today and explained the disturbing changes in the house. If he had done so before a great deal of unpleasant feeling would have been saved. I hope some day before long to come myself to see the work. Meantime the status quo is restored."32

In the fall of 1941, Wright did just that, and reportedly later christened the home his "favorite small house."33

Earth and Trees and Sky

At last, what had so moved Winckler at the Jacobs House was now hers: earth and trees and sky all at once.

The resulting structure embraced simplicity and efficiency, featuring an open floor plan, built-in furniture, and large windows that connected the interior to the surrounding landscape. The house reflected Wright’s belief in creating spaces that encouraged harmony between people and their environment, aligning perfectly with Goetsch and Winckler’s modernist values.

“Goetsch-Winckler house”, Oct. 19, 1940. Cropped from original.

Courtesy the Archives of Michigan Digital Collections.

Often considered one of Wright’s most elegant Usonian homes in both form and function, the Goetsch–Winckler house is a quintessential example of Wright’s vision for decentralized, affordable, and harmonious American living for the everyman—and everywoman.

Unadulterated by the excesses of the postwar economic boom, the house is free of superfluous ornamentation and unnecessary extravagance. It is a house stripped to its bare essentials—unapologetically simple in construction, yet exquisite in form and entirely functional.

More than a model of Usonian design, the house reflects Wright’s belief that dignified, affordable housing should be accessible to those of modest means.

Wright Again

On July 29, 1947—seven years after construction—Goetsch and Winckler, feeling they were outgrowing their space, wrote to Wright and expressed interest in adding a third bedroom.

Wright obliged and sent them an altered floorplan that tucked a third bedroom behind Winckler’s, accessed by a narrow hallway extending behind the brick privacy wall to the north. However, it was quickly determined that the addition would encroach too closely on the property line, and the plan was ultimately never realized.

However, Goetsch and Winckler proposed a more ambitious idea: they would have Wright design them a larger home.

In November 1947, Wright was invited to give a lecture at Michigan State. While in the area, he visited Goetsch and Winckler and accompanied them to a new property they had purchased in the area, intended as the site for their next home.

By August 1948, a contour map had been completed. Goetsch and Winckler requested a more compact design with either three bedrooms or two bedrooms and a studio, as well as storage and low shelving throughout. A few days later, Wright delivered final schematic plans.

This time, financing was not the obstacle—mortgage brokers were eager to support the project. The challenge lay in securing a builder. It was not until March 1953 that they were able to hire the Chamberlain Taylor Construction Company. Unfortunately, even after incorporating cost-saving substitutions, the estimated cost still remained prohibitively high.

Though only a decade had passed since the original Usonia II project, the climate had changed. Following the success of Wright’s Fallingwater and the postwar economic boom, Wright had become increasingly sought after by wealthy clients. His focus had shifted away from affordable, modest homes for the everyman. The new design, while beautiful, was too large, too elaborate, and ultimately beyond Goetsch and Winckler’s means. They had been priced out of Wright’s work, and the project was abandoned.

Though the home was never built, advances in computer graphics and 3D modeling have since made it possible to envision what might have been.

Render by Hugo Avila / Avila Arquitectos

Legacy

While their homes represented their shared vision, Goetsch and Winckler’s story is equally about their partnership and determination to live life on their own terms. As unmarried women in a time when societal norms often limited their choices, they built a life that prioritized their professional goals and creative ambitions.

Their collaboration with Wright resulted in a home that exemplifies modernist principles in everyday living. Their shared vision, friendship, and courage to pursue an unconventional path have left a lasting legacy, demonstrating the power of architecture to challenge norms, inspire creativity, and shape the way we live.

Goetsch and Winckler spent thirty-seven years as close friends and confidants. They shared the stresses and joys of planning multiple homes together and, in so doing, they built a bond deeper than many marriages.

Courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ.

Footnotes

- 1 Salome Winckler Wells, telephone interview by Anatole Senkevitch Jr., August 16, 1988, cited in Diane Tepfer, “From Frank Lloyd Wright to E. Fay Jones: Alma Goetsch and Kathrine Winckler, Ordinary Extraordinary Architectural Patrons,” in Affordable Dreams: The Goetsch-Winckler House and Frank Lloyd Wright (East Lansing: Kresge Art Museum, Michigan State University, 1991), 29.

- 2 “Data on Faculty of Michigan State,” Michigan State University News Bureau; information provided by Mary McGuisick, archivist, School of the Art Institute of Chicago; cited in Tepfer, “From Frank Lloyd Wright to E. Fay Jones,” 29.

- 3 Tepfer, “From Frank Lloyd Wright to E. Fay Jones,” 29.

- 4 Wells, telephone interview, cited in Tepfer, “From Frank Lloyd Wright to E. Fay Jones,” 31.

- 5 Winckler and Goetsch, East Lansing, to Frank Lloyd Wright, Taliesen, “The Idiosyncracy Letter,” October 25, 1938, in Affordable Dreams, xxiv–xxv.

- 6 Ibid.

- 7 Ibid.

- 8 Tepfer, “From Frank Lloyd Wright to E. Fay Jones,” 33.

- 9 Ibid.

- 10 Ibid.

- 11 Ibid.

- 12 Winckler and Goetsch, “The Idiosyncracy Letter,” xxv.

- 13 Ibid.

- 14 Tepfer, 36.

- 15 Anatole Senkevitch Jr., “Usonia II and the Goetsch-Winckler House: Manifestations of Wright’s Early Vision of Broadacre City”, in Affordable Dreams, 13 and 26n48.

- 16 Tepfer, 35.

- 17 Harold Turner, East Lansing, to Wright, June 14, 1940; cited in Tepfer, 37.

- 18 Cheryl Snay, “Chronology”, in Affordable Dreams, xxi.

- 19 Tepfer, 36.

- 20 Ibid.

- 21 Snay, xxi.

- 22 Tepfer, 35.

- 23 Ibid.

- 24 Winckler to Wright, July 23, 1939; cited in Tepfer, 36.

- 25 Ibid.

- 26 Robert C. Twombly, Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life and His Architecture (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1979), 242.

- 27 Harold Turner to Wright, June 14, 1940; cited in Tepfer, 37.

- 28 Tepfer, 37.

- 29 Snay, xxii.

- 30 Tepfer, 37.

- 31 Ibid.

- 32 Wright to Goetsch and Winckler, August 23, 1940; cited in Senkevitch, 25.

- 33 Susan J. Bandes, foreword to Affordable Dreams, xi.